An homage to Goodwood Revival 2020

Goodwood Revival is a unique three-day festival held annually in September that recreates the 1940s, 50s, and 60s era of motorsport, with vintage cars, aircraft, fashion, and music celebrating the circuit’s original period between 1948-1966. Held on the grounds of the Goodwood Estate in Chichester, West Sussex, UK, over 150,000 vintage enthusiasts are encouraged to dress in period clothes to help immerse themselves in a historic car race day.

My family and I had booked to attend the Goodwood Revival finals day on Sunday, 13th September 2020, however, due to efforts to fight the coronavirus pandemic, the event has sadly been postponed until 2021. The Revival attracts such large crowds of spectators that enforced social distancing measures would have impaired the visitor’s enjoyment of the event.

Watch the greatest Revival races online from 11th-13th September 2020

Despite being unable to hold the event this year, the Goodwood team has searched the archive and selected the greatest races from the history of the Revival to stream online over 11-13th September 2020. Fans can still immerse themselves in the spirit of Goodwood Revival by tuning in from 10:00 am on the Goodwood Road and Racing website and on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Goodwood SpeedWeek, 16th-18th October 2020

Goodwood is also taking the opportunity to preview Goodwood SpeedWeek presented by Mastercard. Held without spectators at Goodwood Motor Circuit, this inaugural event will combine the best aspects from the Revival, the Festival of Speed, and their Members’ Meetings to add to its exclusivity.

Annual Revival favourites such as the RAC TT Celebration for GT cars and the Grand Prix race for the Goodwood Trophy, as well as supercar debuts and new car reveals from the Festival of Speed. Cars will leave the circuit to use areas normally reserved for spectators or buildings. There will also be the first-ever set of rally stages on both tarmac and gravel within the Circuit, gathering cars that represent nearly half a century of the World Rally Championship.

The event will be streamed live through the Goodwood Road and Racing website and their social media channels on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Viewers and fans will be able to get involved by participating in competitions, virtual polls, quizzes, and race predictions.

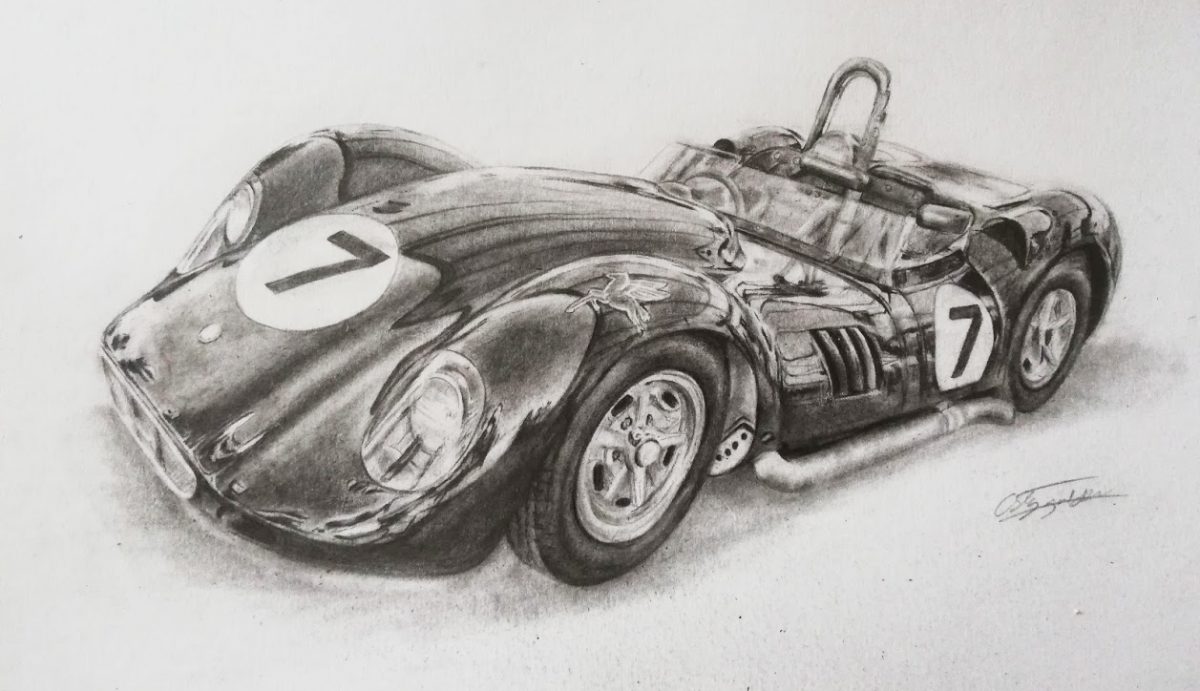

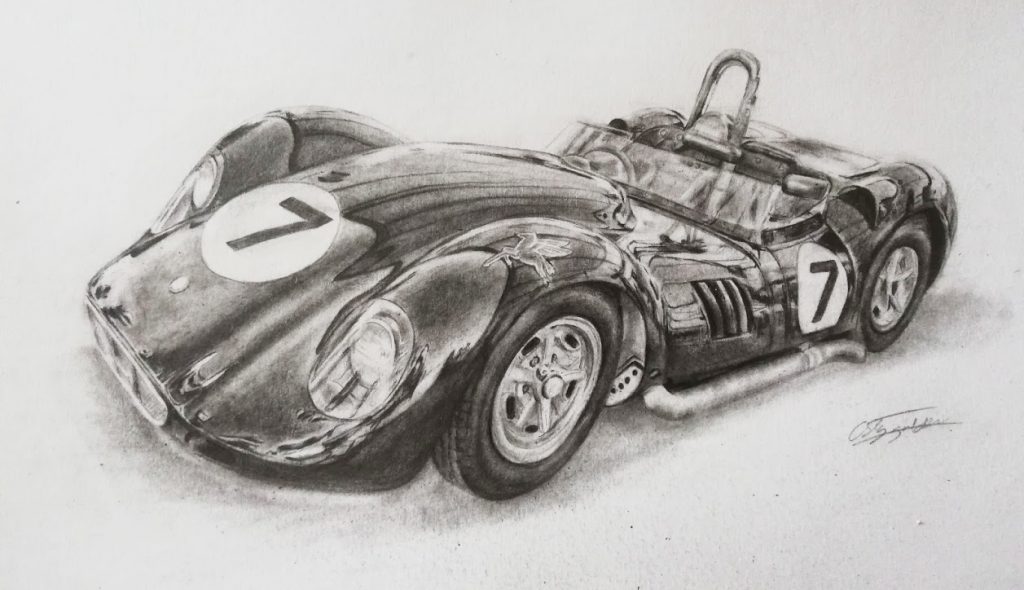

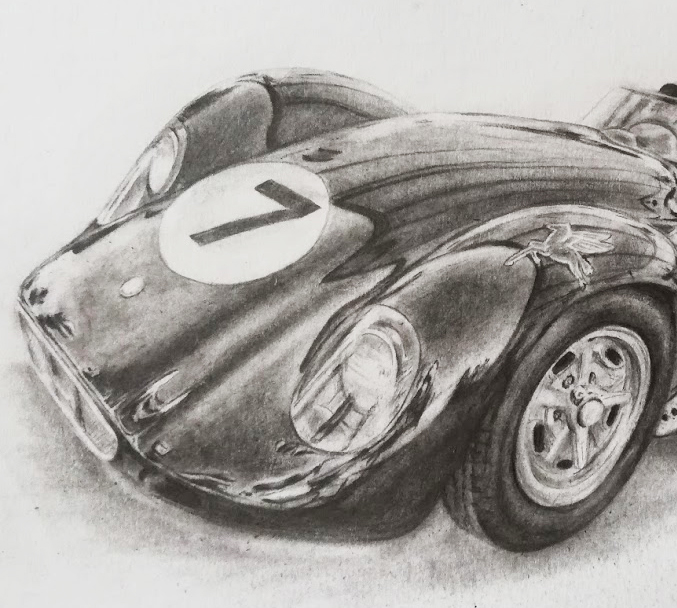

Why I drew the 1958 Lister-Chevrolet ‘Knobbly’ from the Revival

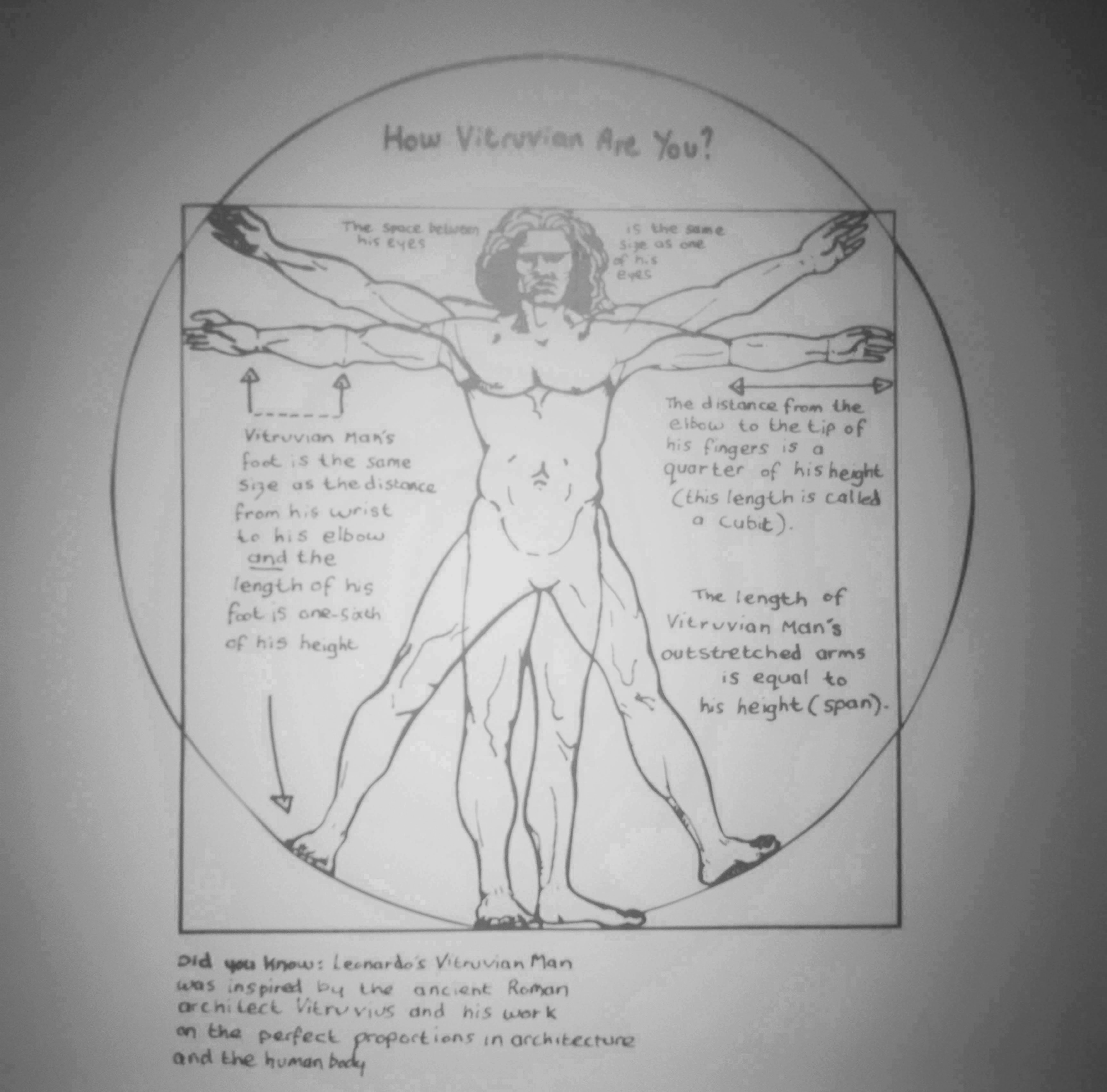

I had already decided to draw several classic cars, supercars, and motorbikes over a few months in the summer, due to a client’s interest in a commission. It also happened to be the birthday of a family member and taking the Revival as inspiration, I drew the 1958 Lister-Chevrolet ‘Knobbly’ in pencil as a gift.

There were many beautiful classic cars at Goodwood Revival, but I chose to draw the 1958 Lister-Chevrolet ‘Knobbly’ as its aerodynamic design, sleek, elongated curves, side exhaust pipes, and unique appearance immediately appealed to me. It was also one of the historic cars racing that day. This particular model caught my eye just before it was due to race on the circuit. I changed the racing number to a 7 as I knew it was the favourite number of the person for whom I gifted the drawing. I thought that a pencil drawing would give a handcrafted and classic, vintage look, as opposed to an oil painting in colour.

I am naturally inclined towards vintage and classic cars, possibly because I have been raised in a family that has enjoyed, collected, and driven classic cars over the years. However, as a fine artist, I think that classic car designs have a sophisticated degree of individuality and are incredibly beautiful; their handcrafted look appears as a work of art. I will admit that classic cars are not necessarily the most practical, but they are beautiful to look at and the feeling you get when driving or being driven in one adds far more to the driving experience.

Lister Motor Company

Founded by Brian Lister in 1951, Lister Motor Company is Britain’s oldest car racing manufacturer and was the country’s most successful sports racing car of the 1950s; it won almost every circuit in the UK and was virtually unbeaten overseas. It is now perhaps the most respected historic race car manufacturer in the world.

Lister Classics is a division of the Lister Motor Company and was founded by Father and son team, Andrew and Lawrence Whittaker, who purchased the company in 2013 to continue building, restoring, and selling a variety of historic racing cars and tuned Jaguar vehicles. You can follow Lister’s official social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Goodwood Revival Fashion

As a gloriously fun step back in time, Goodwood Revival celebrates not only the cars of the 40s-60s eras but also the fashion styles. For anyone who loves vintage fashion, Goodwood Revival is a wonderful event to immerse yourself in.

The Goodwood Revival website has various site pages dedicated to vintage fashion, with ladies and gentlemen style guides for the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. There are also a few websites that provide style guides for Goodwood Revival specifically, such as the House of Foxy which gives advice on the ’40s and ’50s clothes for women.

Goodwood Motorsport Events 2021

To find out more about attending the Goodwood Revival and Festival of Speed events in 2021, visit Goodwood’s website to sign up for ticket alerts.