‘Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art.’ Leonardo da Vinci

I recently had the pleasure of attending ‘Leonardo da Vinci: A life in drawing,’ at Southampton City Art Gallery, which ran from 1 February to 6 May 2019.

To mark 500 years since his death, 144 of the renaissance master’s greatest drawings in the Royal Collection were on display simultaneously at 12 exhibitions across the UK, part of a nationwide event to give the widest ever UK audience the opportunity to see his work.

At his death in 1519, Leonardo bequeathed his drawings and notebooks to his pupil Francesco Melzi. In 1580, the sculptor Pompeo Leoni acquired Leonardo’s drawings from Melzi’s son and mounted them on two albums, one of which was in England by 1630, in the Earl of Arundel’s collection. Within fifty years the album entered the Royal Collection, having been acquired by King Charles II, possibly as a gift. The drawings were removed from the album during Queen Victoria’s reign and mounted individually. In the twentieth century, many were stamped with Edward VII’s cipher. Housed securely in the Queen’s vaults at Windsor Castle for three successive centuries, these intricate drawings reveal an unparalleled insight into Leonardo’s investigations and the workings of his mind.

Arguably one of the world’s most recognisable and revered names in the history of art, Leonardo da Vinci is without a doubt a tour de force of creativity and artistic genius that has surpassed his own era. Leonardo was a polymath and epitomised the ideal of the renaissance man and the French ‘rebirth’, displaying exceptional talent and an effortless ability to adapt and excel in every discipline he set his mind to.

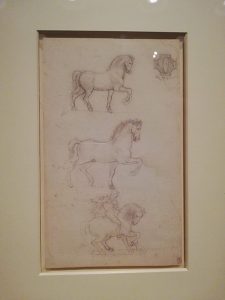

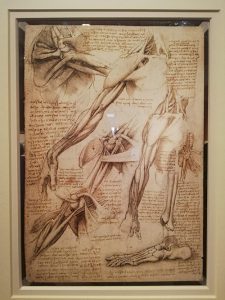

Twelve selected drawings in the exhibition at Southampton City Gallery reflected the range his interest, from sculpture, painting, architecture, music, anatomy, engineering, geology, botany and cartography; each exquisite drawing was recorded meticulously in pen and ink, red and black chalks, watercolour and metalpoint. All his drawings were executed on paper made from pulped clothing rags.

New information into Leonardo’s techniques and creative processes has been made possible by scientific research using non-invasive techniques including ultraviolet imaging, infrared reflectography and X-ray fluorescence.

Leonardo’s preparatory drawings and sketches were never intended to be seen by the public and he would probably be surprised people would want to see them. Even his writings and descriptions scrawled onto pulped clothing are almost inscrutable, being written in mirror form, from right to left. However it is believed he did this so as to not smudge the ink.

Leonardo da Vinci’s view of the world was expansive, he was never limited and this drove him to excel in many areas of learning. The artist believed adamantly in visual evidence being more persuasive than academic argument, and an image could convey knowledge with more accuracy than words.

Leonardo spent hours studying nature and botanical details whilst in his surroundings in Vinci, Italy. His ability to grasp the principles of art and science, and his insight into the human soul, spirit and body, captured the spirit of the times when great advancements were being made and pioneering technology developed.

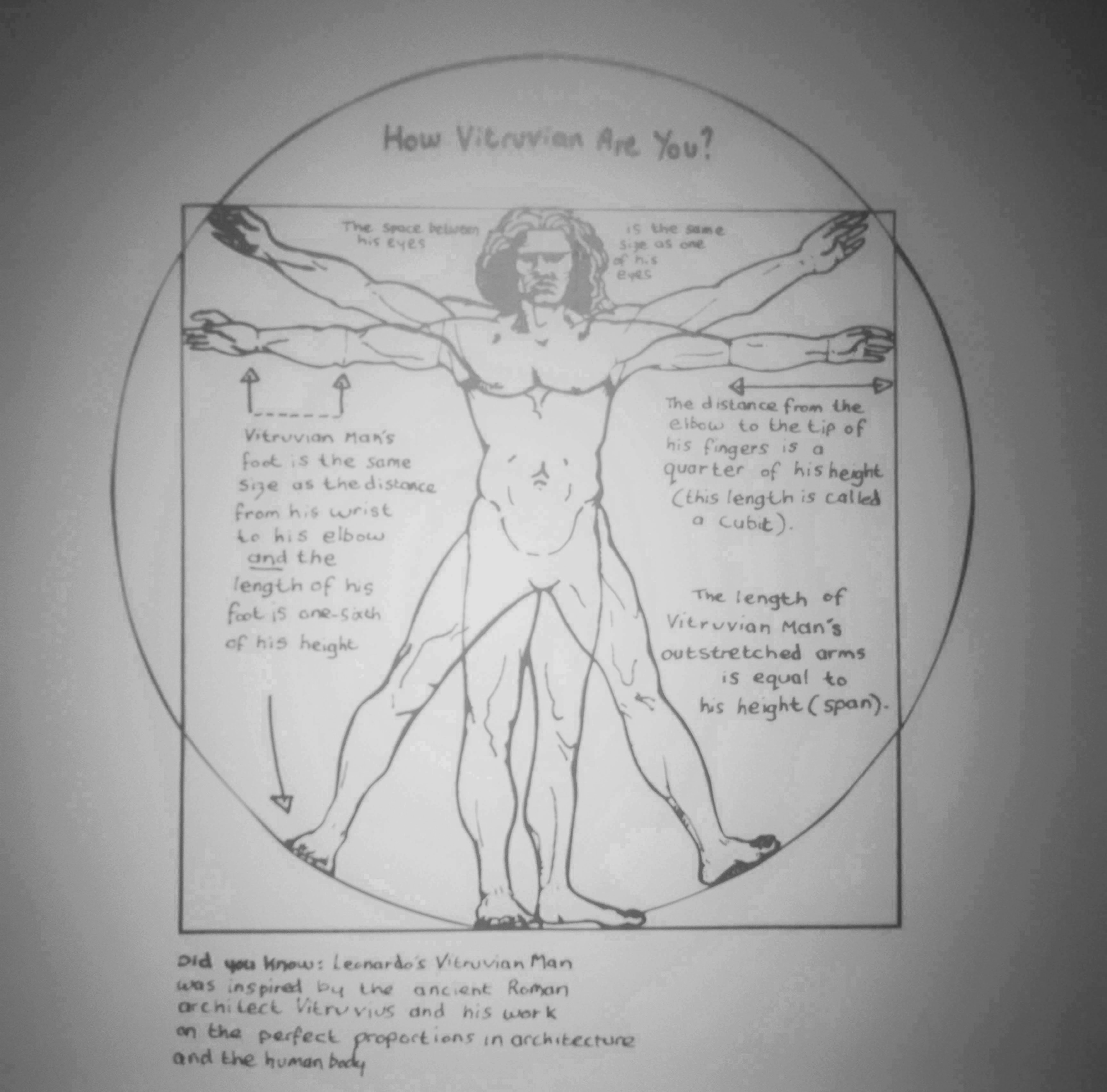

Through careful attention to detail, Leonardo deftly blended mathematics and art into ideal proportions. In Vitruvian man, Leonardo demonstrated his deep understanding of proportions and of the workings of the human body as an analogy of the workings of the universe, uncovering both the ideal symmetry and beauty of the human body mirroring that of the universe. His designs for Vitruvian man were inspired by the ancient Roman architect, Vitruvius and his work on the perfect proportions in architecture and the human body. I like how Leonardo has portrayed the Vitruvian man’s wavy, flowing hair, his expression wild and intense, and his muscular body perfectly poised against the edges of the circle.

Through the ages, the artist has depicted the zeitgeist, the spirit of the times. Their vision of the world has always been like that of a prophet; their extensive time spent in nature and observing detail has given them a deeper level of spiritual understanding of the universe. The very act of drawing and painting is an extension of divine creativity and spiritual expression made tangible.

Leonardo’s preference for a subtle rendering of expression, refined use of shading and changes in tone that is not quite visible is reflected in his art, from the slight smile of the Mona Lisa to the transcendent gaze of the Salvator Mundi, with Christ looking directly into the viewer’s soul. Leonardo captured the human body in a way that revealed their spirit, the individual can never quite be grasped, it evades description and understanding.

In the summer of 2019 (24 May to 13 October), all 144 drawings will be gathered together in a single collection at The Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace, London, followed by a selection of works at The Queen’s Gallery in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, in the winter of 2019-2020.